India-Bangladesh cooperation and connectivity is still win-win

In a passionately if somewhat loosely argued essay in this newspaper a few days ago “Let's talk the talk: Confronting Bangladesh's national security threats,” the writer posited a more muscular and hard-nosed security pivot for Bangladesh. The pitch was predicated on Bangladesh's growing socio-economic heft and strategic needs.

For instance, the writer emphatically -- and correctly -- argues that Myanmar wouldn't have dared to trigger a rush for a million and more Rohingya into Bangladesh had this nation of breakneck growth and ambition taken a preemptive position with national security deterrence against Myanmar in particular and the neighbourhood in general.

.png)

For instance, he argues, does Myanmar dare push the Chin (and I would add, the Nagas) into India with ethnic-cleansing intent? Would Myanmar dare push the Kachin, the Shan (and I would add, the Wa) into China?

No. Because the security heft of these countries and canny bilateral relations ensure what Myanmar took for granted with Bangladesh. Since 2017, Myanmar has literally got away with its grotesque Rohingya project.

To add salt to Bangladesh's sore, two of its key geopolitical and economic partners, India and China, have, because of their interests in Myanmar, raised barely a murmur to mitigate the Rohingya issue or Bangladesh's increasing problems with Rohingya presence on its territory.

So, develop a robust security platform of intent and practice that would drive deterrence, the essay suggested. So far, so good.

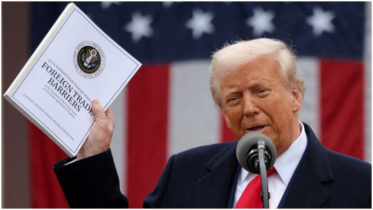

And, the essay also suggested, push back against or negate all impulses like India's plan for a seamless road network through Bangladesh to connect its far-eastern territory to the main Indian peninsula. Indeed, why should Bangladesh connect with “India's impoverished northeastern seven sisters?”

“The truth is crystal clear,” the essay harrumphed. “The economic carrot is an eyewash here, the reality is security.” As India perceives China as a threat, “building this connectivity makes perfect sense.”

This is where indicators and ground reality would have served more than emotion that masks the whole truth. Evidence -- a combination of policy, policy implementation, realpolitik, data -- and a quick look at a regional map would have ensured clearer vision. Crystal, really.

Of course, a more robust north-east will help India in its bolstering against China -- even Myanmar, because who knows where adamant states head on which whim?

And of course Bangladesh is useful to India in its intent of making its far-eastern region more socio-economically robust -- and, therefore, more strategically robust.

But there is a lot more in the bilateral mix.

The region is really eight sisters and not seven: Assam, Meghalaya, Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland, Manipur, Tripura, Mizoram, and very strategic Sikkim -- neighbour to Nepal, the Tibetan Autonomous Region, Bhutan, and only a three-hour drive away from being a neighbour to Bangladesh's Panchagarh border corridor that travels north to the commercial hub of Siliguri, and the tea-, timber- and tourism-rich Dooars.

Besides, these eight do not, in point of fact, account for the poorest Indian states. According to Reserve Bank of India's 2020-2021 figures, Sikkim's per capita income in GDP and PPP terms is second only to Goa.

Arunachal Pradesh ranks higher than Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Punjab, and Andhra Pradesh. Mizoram and Nagaland are better off than West Bengal. And when you throw in Tripura the trio perform better than Rajasthan and Odisha. Manipur, Assam and Meghalaya come off better than Jharkhand, Uttar Pradesh and Bihar -- India's sub-par per-capita performers.

Close to $20 billion have been provisioned by the government of India -- spent, work-in-progress, and work to begin -- to construct or upgrade major highways, secondary roads, railways and air connectivity in this region.

When this is combined with a push for industry, services and trade in Assam, a push for services and agri-business across all these eight states, and a push for oil and natural gas in Tripura, Manipur and, imminently, Nagaland, all bolstered by an east-to-west corridor through Indian territory, this region that accounts for about 50 million people and about one-seventh of India's landmass would benefit greatly from a combination of public spending and private and co-operative enterprise. Micro-finance and SME entrepreneurship are already the next big things in this region.

It is difficult to not see this region as a can-go-to market for Bangladeshi manufacturers, traders, and transporters. As far back as the early 1990s -- my 30-year observation and association with South Asian policies, policymakers, businesspersons, political leaders and security experts began then -- I recall high-level meetings in Dhaka where BNP policymakers and practitioners, despite those relatively stressed bilateral times, viewed India's east and northeast as both markets and territories for investment crossflow.

And as far back as 2014, I was present in Agartala, the capital of Tripura, as Dipu Moni, just a year out of foreign ministership, and advisor to the prime minister, led a delegation to discuss a Bangladesh-Tripura trade and investment future.

All this wasn't done on account of sentiment or weakness, but the prospect of securing bilateral and regional -- even sub-regional -- futures with mutually beneficial trade, investment and partnership. This approach is now, thankfully, largely administration-agnostic for both Bangladesh and India.

As to transshipment between Indian territories through this country: Bangladeshi ships, barges, trains and trucks carry transshipment goods from Bangladesh's western border to its eastern border, or the other way round.

This is as it should be because Bangladesh must benefit from transshipment as it saves transportation time and cost of an extra 1,000 km between, say, Agartala and Kolkata than a direct route through Bangladesh. Regional and sub-regional business and practices must have local buy-in and local benefit.

As it happens, this same route takes -- and would continue to take -- Bangladeshi products both east and west into India.

Bangladesh has signed a free-trade agreement with Bhutan. Two-way trade naturally travels through the Panchagarh corridor -- and, in future, perhaps other corridors, such as via Sylhet-Shillong-Guwahati.

The easiest ingress and egress for trade, preferential or otherwise, with Nepal, will benefit from similar corridors.

India has offered Indian ports and railways for Bangladesh's third country exports to Nepal and Bhutan. This is all either fait accompli or work-in-progress.

Bangladesh purchases electricity from plants in West Bengal and Tripura. As and when it begins to purchase electricity from Bhutan and Nepal, it will flow to Bangladesh -- readily, as assured by India -- through India's power grid.

Waterways as an aspect of bilateral maritime trade is active and a boost-in-progress. The Asian Highways 1 and 2 -- albeit aspirational and long into the future -- looks at Bangladesh as a regional link.

It is planned to be used by Indian goods and people like Asian and global goods and people -- and Bangladeshi goods and people -- as envisaged by free-trade and global connectivity idealists. Either the Asian Highway works for all or it works for nobody.

In this scenario, to view an east-west transport corridor through Bangladesh as a purely China-oriented play is to be unifocal.

In any case, India's China doctrine has evolved in scenarios with and without Bangladesh -- right from its East Pakistan avatar and later, during times of relatively abrasive relationship with Bangladeshi administrations of the day.

In the north-east, for instance, India's play has long gone from managing internal conflicts to looking at China. India's entire eastern arc (West Bengal, Sikkim, Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland, et al) is now geared towards China, right from placement of missiles and aircraft to stationing of troops.

In securing its China-Myanmar axis it is of course useful for India to have Bangladesh provide a socio-economic boost to its northeast. But core security usually calls for a worse-case going it alone: In this case, Bangladesh would at best supplement India's core effort.

“Indian politicians are already asserting that millions of Muslims in India's northeast should also be pushed to Bangladesh,” which will have “catastrophic” consequences for Bangladesh, the afore-referenced essay asserts.

Indeed. But two points here. One: If there is a grand victim of the majoritarian wave in India, it is the Indian, not the Bangladeshi. And two: If one studies Indian politics and its implications for Bangladesh, this would be exposed as rhetoric.

Besides, there being a fence across most of the 4,000 plus km India-Bangladesh border, Bangladesh would need to accept these “pushees,” as it were. To do otherwise could even start a war.

At the least it would destroy India's equilibrium with Bangladesh and threaten to cut off India's northeast from the rest of India through the slim chicken's neck corridor right by Rangpur Division -- a corridor so slim it is possible to walk across it in a day.

India would be preternaturally stupid to let the rhetoric of rightwing satraps come to foreign-policy fruition.

Of course Bangladesh must flex. Not just with India or China or Myanmar but with whomsoever it needs to for whatever it needs to -- and with whatever it can reasonably gain. That's national interest.

Let the flex be to mitigate bilateral water disputes. Let the flex be to push for a justifiable renegotiation of coal pricing with the Adani conglomerate in a power purchase deal with Bangladesh. Let the flex be to work aggressively with India to mitigate climate change and migration crises. Let the flex be to leverage India's G20 presidency to get every possible benefit from technology to energy to trade for Bangladesh. The list is literally endless.

But to deny the mutually beneficial to prove a point, is to deny both the whole truth and a productive future.

Source: Dhaka Tribune